US Quiz of the Month – Abril 2024

Case Report

We present the case of an asymptomatic 83-year-old female with no significant medical history who was referred for a Gastroenterology appointment following the discovery of an incidentaloma during a routine abdominal ultrasound. Upon diagnosis, a discreetly hyperechoic nodular formation adjacent to the posterior contour of the caudate lobe of the liver, measuring 26.5mm, was identified requiring further clarification via CT scan. Subsequent imaging unveiled a nodular formation posterior to the caudate lobe, measuring 36 x 21 mm, demonstrating some heterogeneity and of unspecified etiology, possibly indicating adenopathy. No other formations were reported. Laboratory results, including tumor markers, were unremarkable.

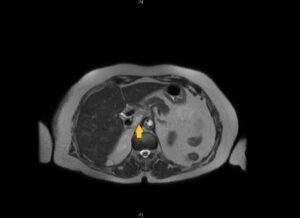

MRI findings showcased an oval-shaped expansive formation with heterogeneous hyperintensity on T2-weighted imaging and restriction on diffusion-weighted imaging, measuring 36 x 16 mm, located between the right pillar of the diaphragm and the retrohepatic inferior vena cava (Fig.1).

Fig.1. Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Axial T2-weighted MRI revealing a 36*16mm oval-shaped expansive formation with heterogeneous hyperintensity, positioned between the right pillar of the diaphragm and the retrohepatic inferior vena cava.

After multidisciplinary discussion, an endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was performed. EUS revealed a nodular formation with well-defined borders posterior to the emergence of the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery, shaping the course of the inferior vena cava. The formation measured approximately 36.7mm in its longest axis, displaying heterogeneity with predominantly echogenic features and exhibiting some peripheral and internal vascularity (Fig.2). EUS-guided fine needle biopsy (EUS-FNB) was done using a 25-G needle (Microtech Trident™ EUS-FNB Needle).

Fig.2 (A&B) Endoscopic ultrasound: Image showing a 36.7 mm nodular formation with well-defined borders posterior to the emergence of the celiac trunk and superior mesenteric artery, displaying heterogeneity with predominantly echogenic features and exhibiting some peripheral and internal vascularity.

What is the most likely diagnosis?

Discussion

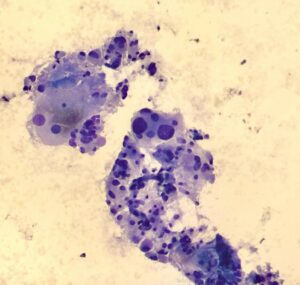

Histopathological assessment of the biopsy sample revealed cells with ample, reticular cytoplasm and rounded or ovoid nuclei with coarse chromatin, indicating some nuclear variability (Fig.3). Immunohistochemical staining was subsequently performed, which demonstrated positivity for chromogranin and synaptophysin with negativity for cytokeratins AE1, AE3, and S100.

Fig.3 Histopathological assessment: Cells with ample, reticular cytoplasm and rounded or ovoid nuclei with coarse chromatin, indicating some nuclear variability, consistent with paraganglioma.

Considering histopathological findings, the diagnosis of primary intra-abdominal paraganglioma was made.

Paragangliomas are rare neuroendocrine tumors originating from either the adrenal medulla or the extra-adrenal sympathetic and parasympathetic ganglia (1). Intra-abdominal paragangliomas are particularly scarce, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 500.000, predominantly sympathetic in origin, and typically located in the paraaortic and paracaval areas, as well as around the inferior mesenteric artery and aortic bifurcation (1,2). While abdominal nonfunctional paragangliomas are rare, their frequency has not been extensively reported (3).

Clinical presentation of paragangliomas can exhibit a wide spectrum, influenced by catecholamine subtypes, ranging from asymptomatic to life-threatening symptoms. Predominant symptoms typically include headaches, palpitations, diaphoresis, and hypertension, attributed to catecholamine excess or the tumor’s mass effect (4). The diagnosis of nonfunctional paragangliomas is frequently delayed when typical symptoms of catecholamine excess are absent, as observed in our incidentally presenting patient (1,2).

Diagnosis typically relies on plasma or urinary metanephrine measurements and nuclear imaging (1). While most paragangliomas are benign, surgical resection is the primary treatment of choice. However, malignant paragangliomas often require a multidisciplinary approach involving endocrinology, oncology, surgery, nuclear medicine, radiotherapy and interventional radiology (1).

Physicians must have high clinical suspicion for paragangliomas when dealing with retroperitoneal tumors located close to the midline in the abdomen, regardless the presence of classic symptoms.

References

- Guo W, Li WW, Chen MJ, Hu LY, Wang XG. Primary intra-abdominal paraganglioma: A case report.World J Clin Cases. 2023 Apr 6;11(10):2276-2281. doi:10.12998/wjcc.v11.i10.2276

- Choi HR, Yap Z, Choi SM, Choi SH, Kim JK, Lee CR, Lee J, Jeong JJ, Nam KH, Chung WY, Kang SW. Long-term outcomes of abdominal paraganglioma. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2020 Dec;99(6):315-319. doi: 10.4174/astr.2020.99.6.315.

- Tanaka, T., Joraku, A., Ishibashi, S. et al.Abdominal nonfunctional paraganglioma in which succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB) immunostaining was performed: a case report. J Med Case Reports 17, 106 (2023).

- Chen HT, Cheng YY, Tsao TF, Peng CM, Hsu JD, Tyan YS. Abdominal Ultrasound in the Detection of an Incidental Paraganglioma. J Med Ultrasound. 2020 Jul 14;29(2):119-122. doi: 10.4103/JMU.JMU_25_20.

Authors

André Ruge Gonçalves1, Antonieta Santos1, Alexandra Fernandes1, Maria Fernanda Cunha2, Helena Vasconcelos1

1 Serviço de Gastrenterologia da Unidade de Saúde Local da Região de Leiria

2 Serviço de Anatomia Patológica da Unidade de Saúde Local da Região de Leiria